The first piece of silverware of the new season is up for grabs on Sunday as France take on Spain in the UEFA Nations League final. Following two thrilling semifinals that saw these two emerge victorious over Belgium and Italy, respectively, the stage is set for an intriguing contest. Here are three things to keep an eye on.

1. France revert to type

What was all the more remarkable about France’s comeback from two goals down to beat Belgium in Turin on Wednesday was how out of type it felt. A team with Kylian Mbappe, Antoine Griezmann and Paul Pogba playing front foot, aggressive football? Not for nothing did L’Equipe label the revival as “extraordinary as it was unexpected” with La Voix Du Nord adding that the result had been “staggering [and] surprising.” It has been a long time indeed since Didier Deschamps’ side have played with such elan.

In that second half, you could see a blueprint for a France side of the future. Mbappe and Karim Benzema were not just lights out in front of goal, without the ball they were leading a press that hemmed the Belgians into their own half, forcing them to go long to Romelu Lukaku and/or concede possession, often near their goal. According to Wyscout tracking data, Belgium lost possession near their goal on 30 occasions in their 3-2 loss. Of those, 22 came in the second half.

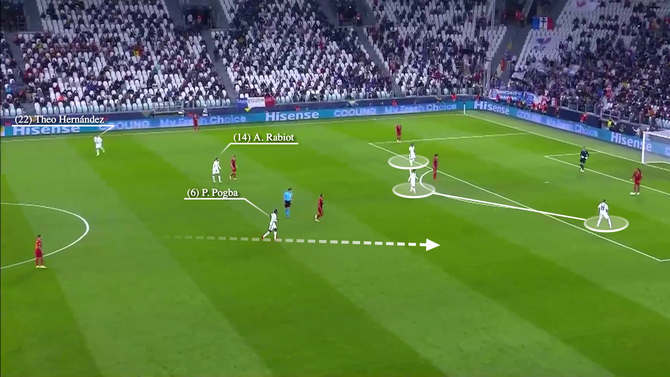

The image above is a sight all too rarely seen in the France side. With the front three pushed high up, the midfielders behind them resolve to push Belgium back into their defensive third, leaving precious few ways to escape. Even the left back in the corner of the shot is not really an option with Pogba pushing towards. Teams have become used to playing against a French opponent that sits deep, inviting them to advance the ball up the field with Les Bleus aiming to win the ball back from there and attack.

With a brisk back three of Jules Kounde, Raphael Varane and Lucas Hernandez behind them, there was no reason why Pogba, Adrien Rabiot and the French wing backs could not squeeze the upper regions of the pitch throughout. Only in the second half did they really resolve to. Match winner Theo Hernandez said: “At halftime, we spoke to each other and said ‘we’re better than them’ and we saw that in the second half. We ate them up in the second half and, thanks to that, we won the match.” He was right. This is a team perfectly capable of winning individual duels across the pitch, both against the Netherlands and Spain.

However, the chances of Deschamps sticking with what worked on Thursday seem rather slim. It is not as if it is news to anyone that France have the players to play a more assertive and expansive style. The default approach under their current management has been reactive, one designed to mitigate risk while trusting that Mbappe or Griezmann can make a feast off scraps at the other end. It has worked to the tune of a World Cup win. It is also perhaps true that Spain might be able to play through the French press with an ease that Belgium did not always show.

Only if France are really struggling are we likely to see a reversion to the template that brought them to the final. Still, it will be useful for Deschamps to know he has it in his back pocket.

2. Busquets to roll back the years

At the highest level of club football, Sergio Busquets increasingly struggles. Rarely the most fleet of foot in recent years, he has struggled to hold the fort against top opposition in his preferred position, the link man between midfield and defense, particularly when he is asked to cover huge tracts of space when other teams are countering. Yet on the international stage, where the pressure is not as organized and the pace of the game drops down somewhat, Busquets can still dictate a match like few others.

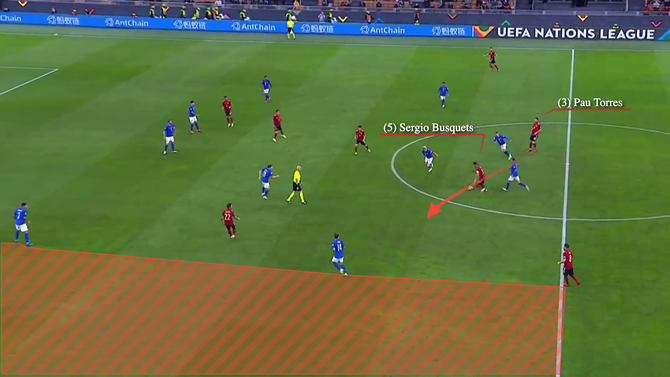

That much was apparent against Italy, one of the few teams that do attempt to put pressure on their opponents at the international level. It did not upset Busquets in any way. According to Wyscout, he attempted 96 passes. He completed 96 passes. This was a clinic in setting the tempo for the Spanish attack, with the No. 5 drawing Italian pressure onto him before switching play into the space his man had vacated.

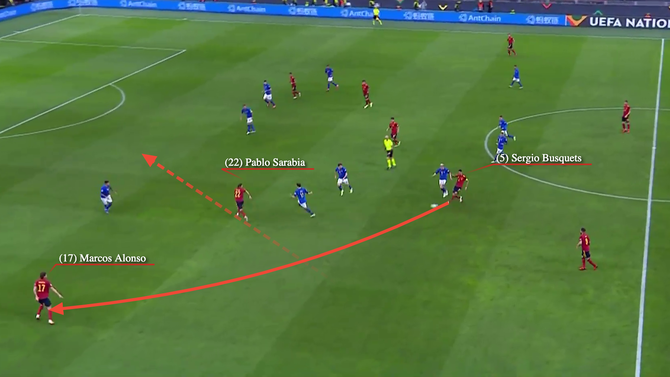

This passage of play might well have resulted in a goal for Mikel Oyarzabal, but for an excellent block from Leonardo Bonucci. It all stems back to Busquets ability to get the ball away from pressure and into a dangerous area. As he moves away (not in the most explosive fashion) the Italian right flank comes inside to pressure, opening space for Marcos Alonso. With Federico Chiesa drawn infield, Giovanni Di Lorenzo has to cover the Spain full back, opening a lane for Pablo Sarabia to drive into.

That left flank could be an intriguing battle ground for the final, not least because Alonso is likely to be as adventurous on Sunday as Yannick Carrasco was in the semis. When Belgium were at their best late in the first half, it came when their wing back was advanced up the pitch to attack his opposite number Benjamin Pavard, who looks ill at ease in a back three/five, with Roberto Martinez moving Eden Hazard infield to occupy right-sided center back Kounde.

It is easy to see how Spain could similarly exploit that spot with their fluid frontline in which Oyarzabal, the nominal starter on the left, drifts around and switches with Sarabia. Alonso is less of a natural in attacking one vs. ones than Carrasco but certainly has the physicality to impose himself on any defender.

As for Busquets, it seems unlikely that he will face the same pressure from France that he did from Italy, at least until Bonucci’s sending off just before the interval. If Deschamps reuses his tactics from the Belgium win, then it would be Griezmann tasked with picking up his former Barcelona teammate; the Frenchman certainly does not press with the energy of the Italian midfield and that is assuming he is asked to do anything like that. If France set up in their low block again, then there will be even more time for the veteran Spaniard to pick his passes and apply a stranglehold on the opposition.

3. This will not be the last winter final

After two semifinals of high drama among four of the best teams in Europe, who could blame UEFA if they looked at the events of the last few days and chose to repeat the trick? The Nations League has been a largely successful competition, bringing much needed competition to the European calendar, but its first finals in Portugal had perhaps been something of a damp squib for everyone but its victorious hosts. Played just a week after the Champions League final the players looked tired and the importance of the fixtures seemed tangential at best. The footballing world was rather drained; the stakes were simply non-existent for a Switzerland vs. England third-place play-off.

Of course, in normal circumstances this would have been another summer tournament, bridging the gap between a Euro 2020 that was not a misnomer and the 2022 World Cup. Instead, COVID-19 forced it to be squeezed in during one of the three international breaks between the start of the season and the end of the calendar year. It is a spot that rather suits it. Suddenly, this is the first major piece of silverware available to some of Europe’s top players this season and perhaps even a chance for someone like Mbappe to make a late push for the Ballon d’Or.

Equally, it offers some degree of footballing significance to an international break that, in Europe at least, feels like it serves no purpose other than to kill burgeoning momentum for the club season. Take the Nations League out of the equation for this international break and what might be the best fixture on the continent? England against Hungary?

Any change to the date of the Nations League finals will not happen immediately. The UEFA calendar is due to return to its previous form in 2023 and Europe’s governing body will surely be loath to sacrifice space in the summer calendar when recent evidence is it will inevitably be filled by something else. But this competition is new enough that there is time to experiment with its format, to tweak it to turn it into the best product for viewers and a tournament that carries weight for its participants. The success of this interlude in the fixture calendar may not be forgotten.