Beginning tonight, the New York Yankees will host the Texas Rangers for a three-game weekend set. It’s fair to write that these teams are located at different ends of the competitive spectrum; the Yankees just had an 11-game winning streak snapped, while the Rangers’ next victory will be their 11th of the season. It’s also fair to write that this matchup presents a golden opportunity to examine Joey Gallo’s struggles since the Rangers traded him (and pitcher Joely Rodríguez) to the Yankees last summer in a deal that netted Texas four prospects: pitcher Glenn Otto, infielders Ezequiel Duran and Josh Smith, and utility player Trevor Hauver.

At the time of the trade, Gallo appeared to be a high-quality addition. This author gave the Yankees an “A” for their part of the deal, praising Gallo’s elite raw strength and improving plate approach as reasons to overlook his high strikeout rate. This author noted, too, that Gallo was different from the standard-issue three-true-outcome sluggers of the past because he had more athleticism and could provide greater value defensively and on the basepaths. Factor in how Yankee Stadium’s dimensions cater to left-handed hitters, and on paper it seemed like a beautiful pairing.

Almost a year later, the Yankees are still waiting for that to translate to results.

Gallo entered Friday having hit .167/.299/.389 in 80 games with the Yankees. His OPS+ in pinstripes, 91, sits well below the 117 mark he posted with the Rangers. His strikeout rate has, improbably, swollen from 36.7 percent to 39.2 percent. Even his home-run rate, which seemed like a given to increase, has moved in the wrong direction: instead of homering every 12.6 at-bats, he’s up to one every 15.8.

Gallo hasn’t played like a star since joining the Yankees. This year in particular, he’s performed like someone who will have to settle for a one-year deal once he qualifies for free agency at season’s end. How did things get this bad? Let’s take a look at three theories behind Gallo’s lacking play, and whether there’s any hope for a turnaround.

Theory No. 1: Gallo is being hurt more by the shift

When you think about the likeliest outcomes for a Gallo plate appearance, you think about strikeouts, walks, home runs, and pulling the ball into the overshift. It’s no secret; opponents have learned over the years that Gallo’s efficacy can be reduced by stacking defenders on the second-base side of the bag. A reasonable thought, then, holds that Gallo’s downfall stems in part from a change in shifting philosophy: either the introduction of more shifts, or, perhaps, the introduction of better shifts.

We can state for certain that the former isn’t true, at least according to Statcast’s data and definition of a shift. Believe it or not, Gallo is actually being shifted less frequently this season than in years past: 93 percent versus either 95 percent in 2021 or 96.4 percent in 2020. His performance against the shift has worsened, however, with his weighted on-base percentage — or wOBA, a catch-all offensive metric that assigns a more appropriate value to OBP than OPS does — sitting at a career-worst .270. For perspective, Gallo has never finished a season with a mark lower than .293:

|

2017 |

82% |

.365 |

|

2018 |

84% |

.330 |

|

2019 |

96% |

.390 |

|

2020 |

96% |

.293 |

|

2021 |

95% |

.350 |

|

2022 |

93% |

.270 |

So, it’s not an increase in shift quantity. What about quality? Below, you can compare Gallo’s defensive positioning heatmaps for 2021 and 2022. Pay close attention to the outfielders, who seem to be moving around more this year than last — at times even creating space for a fourth outfielder to shrink the green space available to Gallo.

Statcast does not publicly display how often a batter is facing a four-outfielder alignment, nor is there any easy way to quantify the changes. The best we can do here is tease out how effective the increased outfield movement has been is by using a combination of results-based analysis and anecdotal evidence.

It’s a small sample size and whatnot, but Gallo’s performance on batted-ball types is different this season than in the recent past. His batting average on balls classified as “grounders” is .273 this season, up from his norm; his batting average on balls classified as either “liners” or fly balls,” conversely, is down to .409:

|

2019 |

.235 |

.628 |

|

2020 |

.161 |

.466 |

|

2021 |

.181 |

.514 |

|

2022 |

.273 |

.409 |

As for anecdotal evidence, consider this single that would’ve been a double had the Blue Jays not had the ability to position their right fielder so close to the foul line. Or this fly out against the Tigers that may have landed and bounced to the wall if not for a four-outfielder alignment. (He’s also had some poor luck, like this pop-up to left that stayed up a little too long, or this line drive hit to the only outfielder in the city block.)

All of this to say that our hunch — and it’s just that — is that if Gallo has been affected by the shift more this season than normal, it’s not been in the way you usually envision, or him grounding out to an infielder stationed in shallow right.

Theory No. 2: Gallo has lost the game of adjustments

Not to go all existentialist here, but defensive positioning is at its root just one kind of adjustment teams make to hitters. Others are contained in the gameplans pitchers and catchers execute on an at-bat by at-bat basis. Hitters, in turn, have to make their own adjustments. Whomever can counter quicker and better will have a longer career.

Pitchers have indeed altered how they approach Gallo in a few notable ways. Foremost, they’re throwing him far fewer fastballs. In each of the past three seasons, he’d seen at least 49 percent heaters; this year, that rate is just 40.6 percent. They’re also locating those fastballs in different areas, with a greater emphasis on elevating the pitch and keeping it on the outer half of the plate (i.e. away from him).

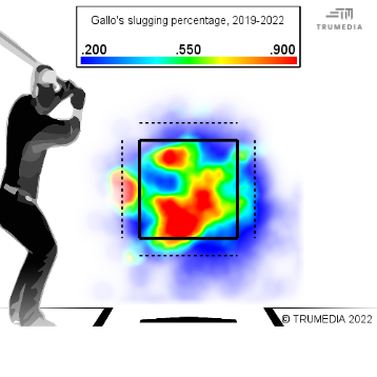

On a related note, here’s Gallo’s slugging percentage heatmap dating back to 2019:

Gallo’s hot spots, so to speak, are … down and either inside or over the middle — or the exact areas where he’s seeing fewer fastballs.

Gallo has attempted to adjust in his own right by altering his swing and his approach. He’s lowered his hands and set them up farther from his body, likely so he has a better chance of hitting a pitch that’s either up or away from him:

Gallo is also swinging more and chasing more pitches outside of the zone. Those alterations have not led to an increased amount of contact (of course they haven’t) and they haven’t been in response to seeing more pitches thrown within the zone. If one were drawing a composite sketch of a pressing hitter, they could do worse than to follow those trends.

There’s one other adjustment worth talking about as it pertains to Gallo’s struggles.

Theory No. 3: Gallo has been hurt by the ball

Could it be that one of Gallo’s biggest issues is the baseball itself? As Zach Crizer of Yahoo! Sports explained earlier this week, line drives have remained valuable while “the value of super high flies in this range has all but totally tanked.” (Defined as those being launched within the 20 to 35 degrees window.) Crizer also concluded that the fly ball hitters who would suffer the least are those who pull the ball at high exit velocities, like Gallo’s Yankees teammate Aaron Judge.

Here’s where things get interesting. You would expect Gallo to be fine; he’s known for pulling the ball (hence the shifts he sees) at high velocities (hence the home runs he hits). Yet Gallo is noticeably pulling the ball in the air less frequently this season than he normally would, with those fly balls (remember, line drives aren’t as impacted by the deadened ball) instead heading to center field. Take a look:

| 2019 | 42.6% | 38.3% |

19.1% |

|

2020 |

42.1% |

39.5% |

18.4% |

|

2021 |

33.3% |

41.2% |

25.5% |

|

2022 |

28.6% |

50.0% |

21.4% |

Maybe that helps to explain why Gallo is miserably underperforming his ball-tracking data. It may not feel like it, but he’s in a select group of hitters (minimum 50 plate appearances) who rank in the 90th percentile or better in both: 1) percentage of batted balls traveling 95 mph or faster; and 2) percentage of batted balls launched between 10 and 30 degrees. (In layman’s terms: these players are barreling balls often.) Here is the full list of those hitters, along with their seasonal OPS+ entering Thursday:

- Yordan Alvarez, 195

- Ji-Man Choi, 235

- Bryce Harper, 116

- Joey Gallo, 88

Obviously this is rife with selection bias — oh, round numbers! — but through that lens Gallo’s formula should be producing far better results than it has to date.

The interplay between the above theories help to explain that underperformance, in our estimation that boils down to this: Gallo isn’t playing like his good self because he’s not doing as much damage on balls in the air. He’s not doing as much damage on balls in the air because of the differences in how he’s being pitched and defended, and because he’s having to hit a baseball that won’t reward him unless he does the one thing — pulling the ball in the air — that teams are focused on defending against.

What does that mean for Gallo’s future? It’s hard to say. The baseball could change tomorrow — really, it could — and all the sudden Gallo’s well-struck balls to center could start clearing the fences. Or he could return to his old approach, which may allow him to feast on more mistake pitches that miss their spot and end up in his nitro zone. It’s as hard to forecast as it is easy to understand why there’s mounting frustration surrounding Gallo’s time in New York.